Who wants to watch robots play football?

Why AI's ability to solve complex puzzles still doesn't indicate a mind at work

“The fact that we hear so much about this artificial intelligence being able to ‘understand’ is pretty much our own rhetorical creation,” says Luciano Floridi, founder of Yale’s Digital Ethics Center: “It’s like looking at clouds and seeing faces in the clouds or looking at trees and thinking, Well, if they move, grow, and whisper in the forest, they must have wishes, emotions, and plans.”

This week at Public Seminar, Floridi sits down for a conversation with Giannis Perperidis and Alexandros Schismenos about what commentators—and engineers themselves—fail to understand about artificial intelligence.

On the topic of AI and writing, Laurie Sheck chats with Matthew Kosinski about interrogating the experience of thinking—amidst an onslaught of information—in Cyborg Fever, her new book of experimental fiction. And Tsering Dolka Gurung interviews English professor and former Microsoft engineer Dennis Yi Tenen about the writing technologies from which AI developed, such as Buddhist divination practices.

Finally, Andrew Joseph Pegoda examines Governor Greg Abbott’s wheelchair as a politically charged technology that reveals a pervasive culture of “cripnormativity.”

Writing Was Always Magical

Tsering Dolka Gurung and Dennis Yi Tenen

Dennis Yi Tenen: For the author of the future, writing will involve an orchestration of resources. A contemporary film director, for example, is not doing everything in the film. She hires a team. She orchestrates. “You do this. You stand over there, this camera moves like this.” There are post-edits. Writing was sequentially putting pen to paper. But writing tomorrow will look more like directing a film. You’re orchestrating resources, generating something, putting it through one filter, applying another filter, tuning stuff. An image is a signal. Writing is also a signal that you’re putting through a number of transmutations to produce your art.

Great Engineers, Terrible Philosophers

Luciano Floridi, Giannis Perperidis, and Alexandros Schismenos

Luciano Floridi: When John Searle says that computers are syntactic engines, he is absolutely right. Any kind of computational entity, any Turing machine, including any form of AI, treats data in terms of necessary deductions or probabilities. It is the distinction between syntax (how to combine elements according to which regularities) and semantics (what the elements and their combination may mean). Data processing systems can do extraordinary things syntactically, not semantically. Our age will go down in history as the age that discovered how much one can do by syntax in context where we thought only semantics could produce what we want.

The Monster Became My Companion

Matthew Kosinski and Laurie Sheck

Laurie Sheck: In Cyborg Fever, I was interested in exploring what I thought of as two different kinds of information. The first felt nourishing and often beautiful—facts one comes upon that help explain the world, bring it closer, lay bare to an extent its mysteries and complexities. These facts are connected to a sense of awe. It is these that often appear on Funes’s computer screen—quotes from scientists, from astronauts, facts about the passionflower, the behavior of particles and antiparticles. The second feels more chilling to me—information flooding into our brains from our various devices, and the attendant sense of randomness and glut. What is this doing to us—this constant glut of content, this ubiquitous attachment to our laptops and phones?

You might have noticed that Public Seminar is always free to read. That’s because we think democracy is fueled by rigorous intellectual debate being accessible to everybody. If you like what we’re doing, why not make a tax-deductible gift?

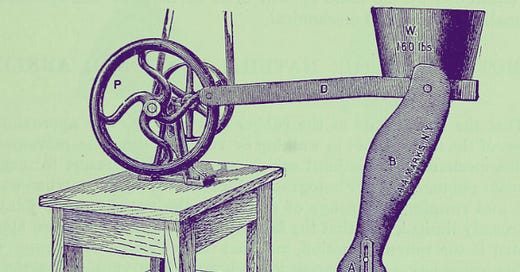

Greg Abbott’s Wheelchair

Andrew Joseph Pegoda

Even assistive technologies serve as cripnormative markers. A motorized wheelchair would indicate less physical strength and greater dependency to the public imagination, making it less acceptable in a cripnormative framework. A heavier person needing a larger wheelchair would be less acceptable, as would a person who requires assistance moving his wheelchair. Abbott’s wheelchair, by contrast, is highly preferable: It’s a small, manual chair, and he operates it himself. In cripnormative fashion, this shows our ableist public that Abbott is making the maximum effort to achieve “rugged individualism.”