Then and there?

Can our past to deliver us from the present?

At Public Seminar, we’re thinking about José Esteban Muñoz’s injunction to see and feel beyond the “prison house” of the present. “We must strive, in the face of the here and now’s totalizing rendering of reality, to think and feel a then and there,” Muñoz wrote. This week, our contributors reckon with the short-sighted political ideologies that led to today’s quagmire in the hope of retracing their way to a then and there.

Manousha Dhiwaghar revisits the “prophetic ethics” of Judah Magnes, the rabbi and pacifist who spent the 1930s and 40s advocating for a binational Jewish-Arab state in Palestine.

A few decades later, a teenage Göran Rosenberg enjoyed a Labor Zionist Kibbutz as “a boy’s fantasy, a scout’s dream, an endless summer camp.” But then, in the aftermath of the so-called Six-Day War, Rosenberg met Palestinians for the first time. Coleson Smith describes how Rosenberg’s newly reissued memoir, Israel: A Personal History, blends personal narrative and historical research to explore the author’s disillusionment with the Zionist project.

Meanwhile, Kwach Abonyo argues against interpreting Frantz Fanon’s oft-cited claim that “decolonization is always a violent phenomenon” as nothing more than a call to physical confrontation. “The inner and outer dimensions of revolt were intertwined necessities for Fanon,” Abonyo writes, “each incomplete without the other and each a condition for reclaiming the agency and dignity systematically stripped from the colonized.”

And Bruno Heidlberger arms us against a fascist resurgence by examining the parallels between the ethnic ideologies of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) and those of National Socialism—and the Trump administration’s not-so-hidden sympathy with the movement.

A Lost Utopia

Coleson Smith

In a powerful account of his growing disenchantment with his parent’s conception of Israel as a utopia for Jews, Rosenberg presents Zionism as a flawed vision with a tragic aspect: Far from being inevitable, the modern state of Israel, as he recounts its history, evolved in brutal policies that belied the utopian hopes on which the new nation had been founded in 1948.

Germany Holds Up a Mirror for America

Bruno Heidlberger

The rise of the AfD and the Trump administration’s not-so-hidden sympathy with the movement isn’t just Nazism reanimated. Today’s forms of post-fascism combine ethnic nationalism, religion, and technology in a wide variety of ways, all aimed at the myth of national resurrection. Some Silicon Valley tech billionaires are bewitched by the idea that a new power elite freed from petty laws and regulations can “solve” the world’s problems through the consistent application of new technologies, Christian transcendence, and apocalyptic visions. This hypertrophic self-confidence is a step backward from the Enlightenment.

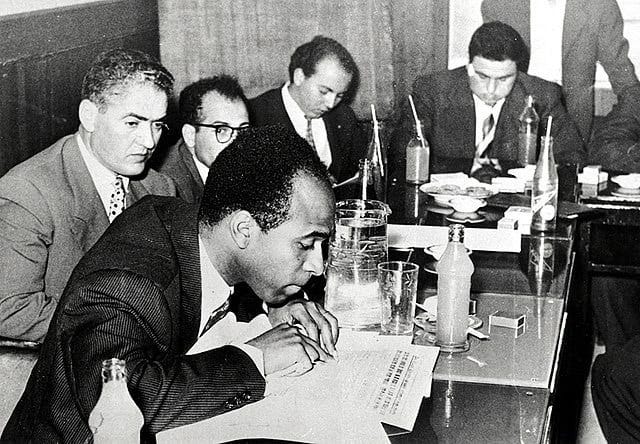

Frantz Fanon and Africa’s Postcolonial Predicament

Kwach Abonyo

Liberation, he argued, had to mean freeing not just a people and a land but each and every single self. Africa got nations, but even the most avowedly revolutionary leaders were not themselves remade into blank slates, and their professed radical humanism did not give rise to a genuinely new human consciousness. That absence still haunts the present.

Judah Magnes: Binationalism as Political Theology

Manousha Dhiwaghar

Magnes died in 1948, the year of Israel’s founding. He did not live to see the consequences of what he had feared—a ruptured holy land—but the myth he carried did not die with him. It remained dormant and wounded in the margins of political discourse.

Today, as new plans for the Gaza Strip take shape, Magnes’s myth returns as a provocation.