The problem with hermits

The politics of fight vs. the philosophy of flight

Should we flee for refuge or fight for it?

This week, William Clare Roberts talks to Gant Roberson about why we need to keep translating Marx. Alex Rossen reviews David E. Cooper’s Pessimism, Quietism, and Nature as Refuge. Nick Johnston and Daniel Kopp discuss the problem of living like a monk without having a monastery in Wim Wenders’s latest film, Perfect Days.

And Charles Bradley reports on what happens when schools, which are supposed to be as safe havens for children, are the targets of military violence.

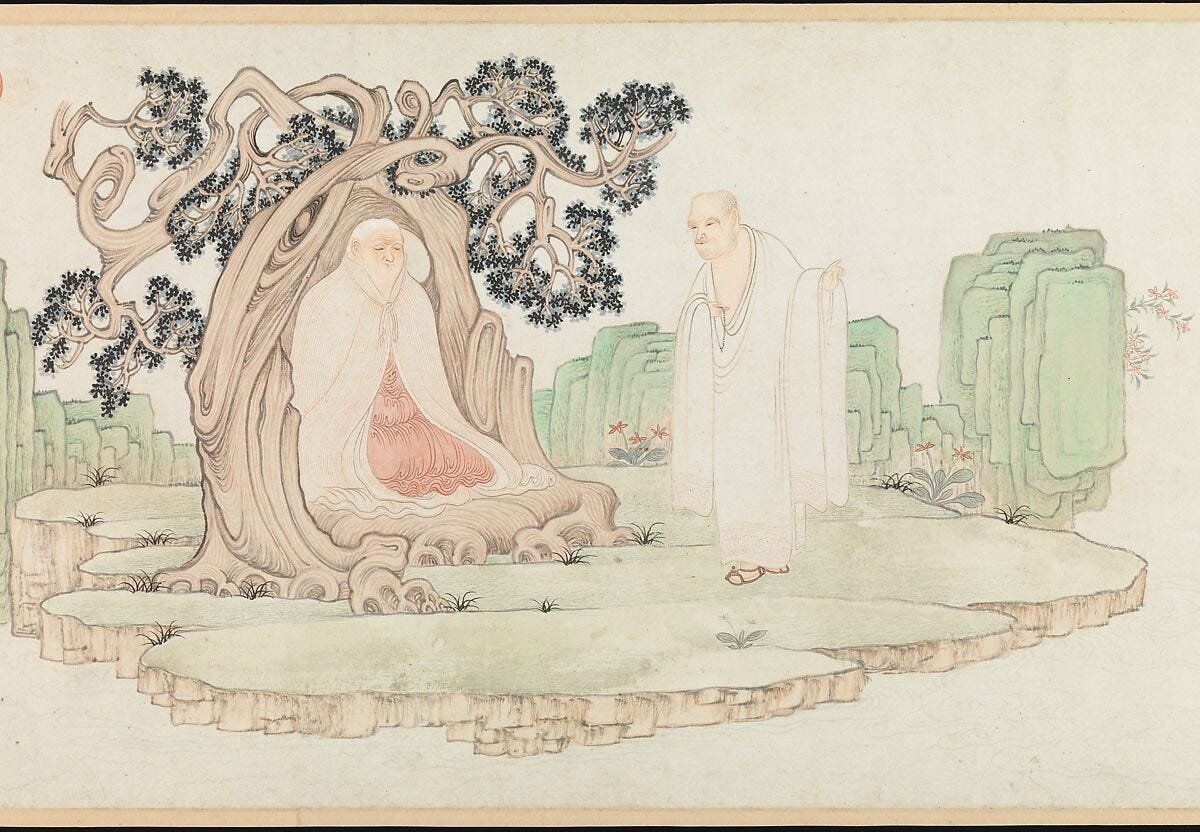

A Monk Without a Monastery

Nicholas Johnston and Daniel Kopp

In an interview, Wenders reluctantly admitted that he had imagined Hirayama as someone who has given up an unhappy life as a wealthy businessman to become the kind of person who notices the “play of leaves and sunlight and shadows moving.” While critics may differ over whether the resulting film is a performance of mindfulness or escapism, they seem to agree that Perfect Days wholeheartedly celebrates Hirayama’s life choice.

Schools Are for Children, Not Soldiers

Charles Bradley

With their schools destroyed, the options for children who decide to stay at home are severely limited: boys regularly end up in the workforce and girls marrying. More extreme yet, in places like Yemen, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, children who have dropped out are commonly recruited into combat service by the very armed groups that occupied their school in the first place.

Misanthropy Is Having a Moment

Alex Rossen

If you asked Cooper what he thought about the Green New Deal, for instance, he might take a line from his book and say: “Perhaps these are sensible answers … [but] … What bearing on my life has the proposal radically to reduce consumption when I know that this won’t happen?” Broad, sweeping proposals like these are just distractions and evasions, he says—away from the only important question one should be asking: “What can I do to change myself?”

Reconstructing Capital

Gant Roberson and William Clare Roberts

William Clare Roberts: Marx thought the Paris Commune was a strategic blunder. He didn’t think that the French working class was in a good position to have this fight. And once the Commune was set up, he was critical of many aspects of how they were running things. But when the Paris Commune was crushed, he nonetheless rushed to the defense of the Commune. And that’s partly because he did appreciate something about what the Commune was doing. He thought that there was a possibility that was relevant to all of those parts of the world that didn’t look at all like Britain. Most places were not nearly as industrialized as Britain, they weren’t nearly as proletarianized as Britain. They looked a lot more like France, where you had pockets of proletarianization, but in the context of a largely peasant working class. Marx saw the Commune as a promising failure and he really wanted to try to learn from that failure and to address the French edition of Capital to a French working class that had also gone through that failure and was in a position maybe now to learn from that failure itself.