Teaching While Black

Public Seminar presents a special double issue on African American scholars working in higher education, with Dwight A. McBride, Cathy J. Cohen, and more

April 28, 2022

Teaching While Black

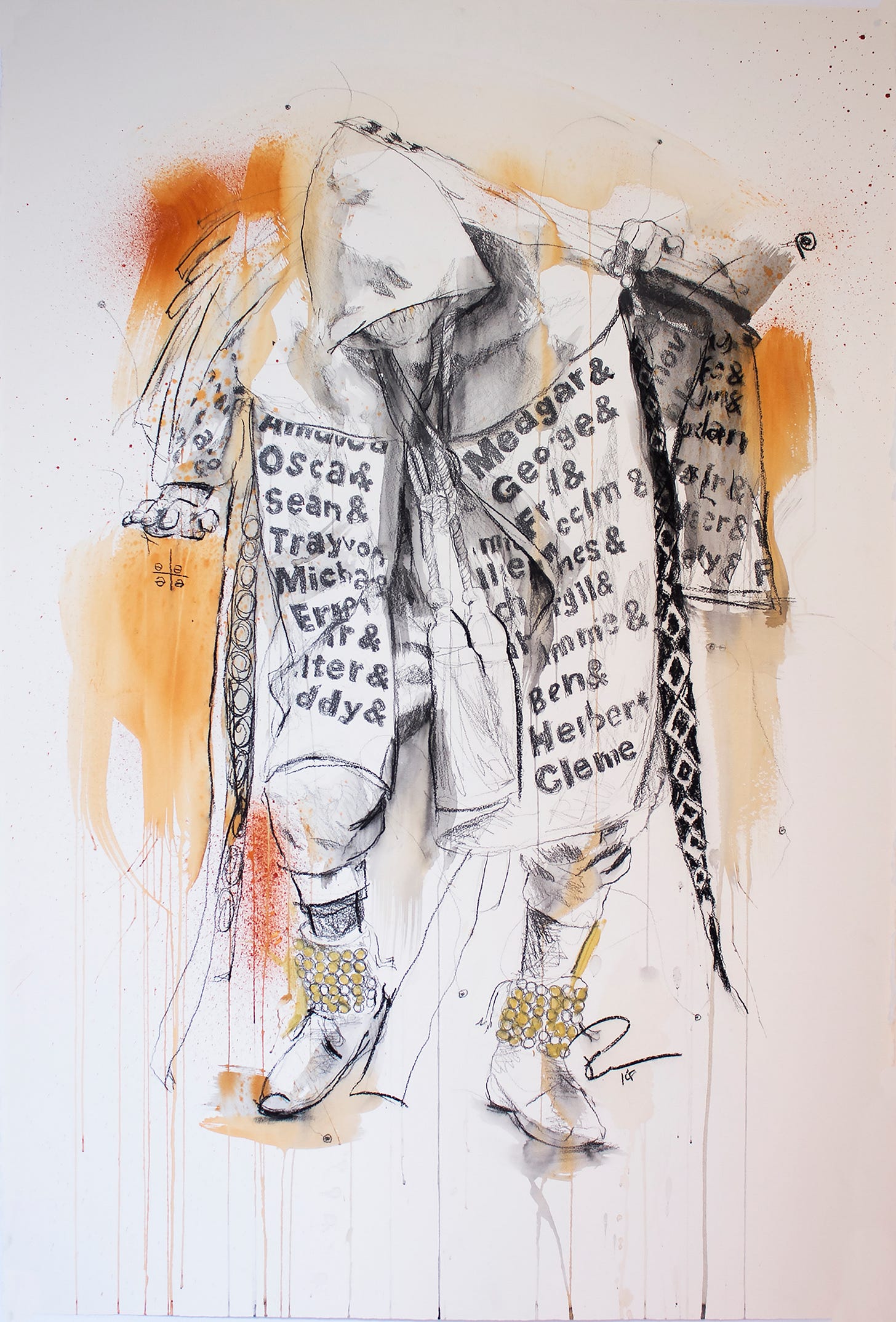

This fortnight’s double issue of Public Seminar is “Teaching While Black,” a symposium that illuminates the experiences of African American scholars working in higher education. Featuring artwork by acclaimed interdisciplinary artist and scholar Dr. Fahamu Pecou, the special issue is co-edited by New School President and University Professor Dwight A. McBride, James Baldwin Review Managing Editor Justin A. Joyce, and Public Seminar Co-Executive Editor Claire Potter.

“As the contributions in this special issue of Public Seminar make abundantly and often painfully clear, teaching as a person of color in the predominately white spaces of higher education presents challenges far beyond the demands of the actual job.” Dwight A. McBride introduces the special issue and discusses the pressures of being a historic “first.”

Erica L. Ball describes how higher education expects Black academics to conform to an unspoken and ever-shifting ideal of Black identity. “Based on my up-close-and-personal experience as a middle-aged Black woman professor, it means that it is possible for one to be perceived as a curiosity by the colleague down the hall, as an ‘Angry Black Woman’ by a dean, as ‘not Black enough’ by some students and ‘too Black’ by others. On more than one occasion I have found myself perceived as multiple Black women (none of whom were actually me) before I even made it from the faculty lot to my office.”

“There is power in choosing to walk away when you know there is nothing that you can do to make things better. It can be truly liberating when you leave behind the frustration and the toxicity that will eventually lead to bitterness, when you know the situation is hopeless.” When asked to prioritize committee service over your own scholarship, Dorothy Brown writes, don’t be afraid to say no.

Beverly Guy-Sheftall recounts how feminism influenced the most difficult decision of her academic career: protesting the Spelman Board of Trustees’ refusal to appoint the college’s first Black woman president. “Because I was untenured, and students were also involved in the protest, I knew that I could, and probably would, lose my job. But I also knew that if I survived and was allowed to remain at Spelman I would continue to practice what I had been preaching to the students who chose to join the small band of faculty engaging in positive social and institutional change.”

In an interview with Claire Potter, Cathy J. Cohen unpacks what it takes to make a university community where Black faculty and students can thrive. “You find institutions that already exist, and you build ones that don’t. At Michigan, I joined other, mostly Black, students engaged in political activism and making demands on the university, and we built an organization called United Coalition Against Racism (UCAR). Many of those people are literally my family, my best friends still.”

“Responding to, and answering, the question ‘Are you sure?’ can be emotionally taxing and precarious: white students can be quite resistant to having their ideas about white supremacy exposed and challenged, particularly when those ideas were delivered through cherished artifacts of their own childhood.” Charles I. Nero shares how he turns white students’ disturbing lack of confidence in his intellectual authority into teaching opportunities.

Enjoying “Teaching While Black,” a special issue from Public Seminar? Why not share it?

“With one foot in and one foot out of academic life, I always questioned how I

was participating in my own destruction by doing this work, allowing the

university—with its handmaidens poised to reinforce extraction—to kill me.” Gina Athena Ulysse examines the unequal division of labor that endangers Black women in the academy.

Sylvester A. Johnson explains how mentorship offers an important chance to address the racial dynamics of the classroom and reassure students that they belong. “As a Black professor, I am especially mindful that the so-called imposter syndrome—feeling out of place and questioning one’s own skills, knowledge, or merit—is a particular threat to Black students.”

“Students smile when they see me in the classroom. The tall Black man from Detroit is now in the academy with his PhD. I lean forward and whisper to them through the syllabus, This course is for you. Designed with you in mind. I find myself nudging students toward excellence. Giving them theory. Spoonfuls. Carefully, yet fastidiously allowing them to taste the words in their own mouths.” Terrance Dean presents a teaching ethic founded on Black love.

Bridgette Baldwin and Davarian L. Baldwin discuss how the false intimacy of white students leaves Black scholars with a crushing sense of objectification. “You walk into the classroom, armed with years of rigorous training and expertise, ready to fulfill your vocation, excited to shape and inspire young minds and to deliver your expertise to the next generation. But quickly you realize that you are an oddity, a curio, the novelty of a Negro in the academy: Look! You are a walking embodiment of contradiction between the life of the mind and the historical caricature of your Black body.”

“Moving back and forth between my research, teaching, and my artistic practice also keeps me from becoming jaded, bored, or Pollyannaish. I understand the rants on social media by those who are frustrated by the corruption, bad deeds, and exploitation endemic to both spaces. For me, however, toggling between these imperfect (yet frequently idealized) institutions keep me clear about the limitations of both, even as I still use them for inspiration.” Lisa B. Thompson recommends a way to teach freedom: model it.

Three years after being granted tenure, Duchess Harris postponed her sabbatical and enrolled in law school: “I felt it was time to apply my political and theoretical beliefs to action-oriented work that expanded rights, opportunities, and privileges for marginalized people, especially women and people of color.”

“Blackness as too much and simultaneously not enough are warring ideas that enter our classrooms. The notion that there is not enough to talk about, that all Black literature is the same, that it is too difficult, too abstract, too Black to discuss, let alone teach in mixed company is rooted in a fear of Blackness.” In an excerpt from Teaching Black (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021), authors Ana-Maurine Lara and drea brown discuss how teachers of Black literature must move beyond traditional methods of instruction.