How does one maintain hope in the midst of such perfidious behavior?

Yes, we can rediscover democracy—and each other

Writing about the desolate stage of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame, the philosopher Theodor Adorno suggested that the play takes place in a world devoid of metaphysical hope: a zone of indifference.

“I don’t think today we’re exactly in a zone of indifference,” replies Elzbieta Matynia: “At least, not yet.” This week at Public Seminar, Matynia shares a personal essay on the integral part hope plays in keeping democracy alive, from Beckett to bridges to revolution without bloodshed.

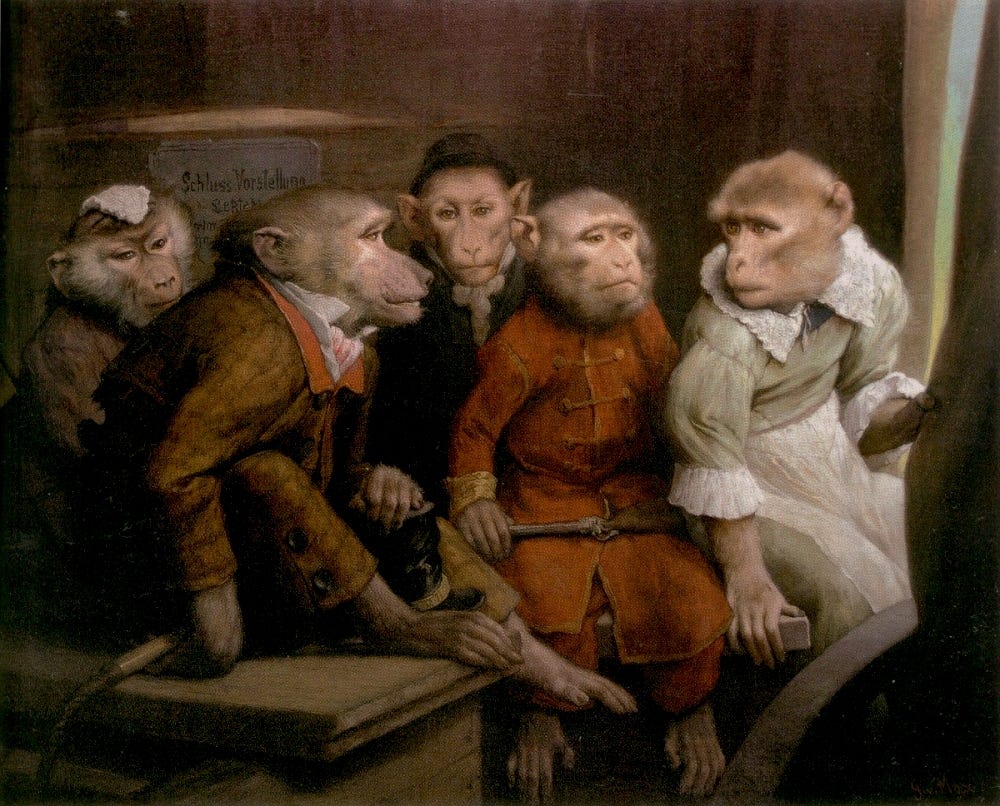

Meanwhile, Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka look at democracy from another angle—namely, how do the rest of the animal kingdom manage the politics of groups?

Democracy’s Endgame?

Elzbieta Matynia

Let me start with one such new beginning that might endow us with the power to make things happen, to create, to enact, to constitute a new social reality: the exercise of a kind of creative imagination, capable not just of passively beholding a bleak work of art, but in a paradoxical response, to react by doing, by acting, not just contemplating.

I experienced it personally, as an aspiring sociologist in Warsaw studying the politics of the underground dissident theater movement in Communist Poland in the wake of the Solidarity trade union uprising of 1980.

It becomes increasingly difficult for me to talk about it afresh, as the story’s been told so many times that whatever is left feels stodgy and dull. But it was not! We—and many, many others—felt so enormously alive and happy in experiencing daily the meaning of solidarity (with a small s) and being able to act upon it.

These years were the formative experience of my life as a citizen—a magnificent gift that I still carry with me. I remember distinctly feeling, with a twinge of regret as I left Poland in 1988 for a scholarship in New York, that I had just left a place of tangible hope.

Ethologies of Animal Politics

Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka

Imagine a herd of wild horses in which some of the mares are expending energy nursing foals and therefore need to eat and drink more than other members of the group. This gives rise to different preferences—some horses might prefer to sleep, while the nursing mothers wish to move to a new grazing spot. What does the herd do? This is not an unusual scenario. Indeed, many kinds of animal communities must make ongoing decisions in the face of diverse interests about when to move, where to go, where to sleep for the night, how best to evade predators and other risks, how to organize eating and mating to avoid conflict, how to play safely, and so on. And it turns out that animal communities have developed a fascinating variety of practices not just for coordinating one-to-one behavior, but also for navigating group-level decisions.