This week at Public Seminar, we’re rethinking narratives of migration and crisis in the United States.

Nina Glick Schiller outlines how the US immigration system has created a super-exploitable workforce. T. Alexander Aleinikoff and Alexandra Délano Alonso chat with Paloma Griffin about centering displacement and dispossession in New Narratives on the Peopling of America. Achilles Kallergis examines why anti-immigrant discourse rings hollow in New York City. And Marco Saavedra describes his ambivalence in painting the Statue of Liberty: “Everyone is from this earth, everyone is Indigenous, everyone is illegal.” With images by Marco Saavedra and Cinthya Santos Briones.

Belonging as Poetry in New Narratives on the Peopling of America

T. Alexander Aleinikoff and Alexandra Délano Alonso in conversation with Paloma Griffin

Aleinikoff: Once you start from a perspective that the current claim of possession itself is problematic, it opens up new possibilities. It gives you a real lever to question that total authority exercised by people who really can’t claim, legally speaking, “good title” to the land that they have. Secondly, dispossession is not just about land, it’s about culture, language, viewpoints. This goes beyond Indigeneity: the central narratives that we’re questioning here and problematizing have attempted to ask people to dispossess themselves of their stories, their ways of being in the world.

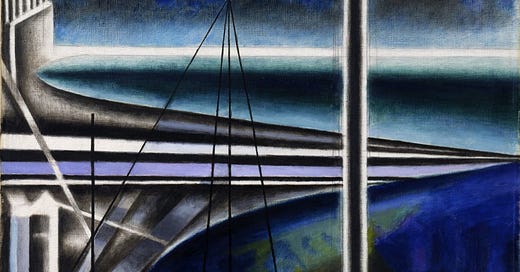

Notes on red liberty

Marco Saavedra

My family and I crossed the border illegally in 1993 and settled 2,700 miles from our ancestral village, but there is a connection in all things native. Unable to return to my native home, I must connect and cry with the native land that adopted me: “by indirections find directions out” (Shakespeare, Hamlet). What was here before cranes, concrete, and crosswalks? What will remain after? I have never found the Hudson River, for example, a fitting name to the body of water I grew closest to, and I find the Mohawk name Ka’nón:no more musical and true.

It’s Not a Migrant Crisis—It’s a Political Crisis

Nina Glick Schiller

I began the collective project of understanding migration in the 1960s by working closely with people who had fled the murderous Haitian Duvalier dictatorship yet didn’t have the right to settle in the United States. At that moment, most migrants came as visitors, overstayed their visas, and joined the workforce as part of what became the millions of people who have been designated undocumented. Transforming an undocumented status was sometimes possible, unlike the situation migrants face today.

New York’s Existential Crisis over Migration

Achilles Kallergis

The new arrivals have acted as a prism, revealing the spectrum of persistent crises that plague New York: the housing crisis, the homelessness crisis, poverty, growing inequality, and the longstanding systemic injustice that vulnerable groups—migrants and citizens—continue to face.